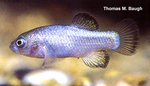

Cyprinodon diabolisDevils Hole Pupfish

Geographic Range

The distribution of Cyprinodon diabolis is restricted solely to a relatively small, isolated limestone shelf in the Devil's Hole Pool in what was previously Nye County, Nevada, in the southwestern United States. In 1952 the Devil's Hole Pool was incorporated into the Death Valley National Monument in California. (Deacon and Deacon Williams, 1991)

Habitat

Cyprinodon diabolis inhabits the Devil's Hole Pool, which is found in the very arid Death Valley in California. Devil's Hole is 2.5 by 3.5 meters in area and is composed of two separate areas. One is a limestone rock shelf that is 3.5 by 5.0 by 0.3 meters deep. The second component is 3.5 by 17.0 meters in area and is of unknown depth. Cyprinodon diabolis resides in the upper 80 feet of the body of water, with half of the population residing on the limestone shelf. This allows maximum sunlight exposure as well as access to food. The temperature of the water stays a constant 33 to 34 degrees C. (Naiman and Soltz, 1981; Ono, et al., 1983)

- Habitat Regions

- temperate

- freshwater

- Terrestrial Biomes

- desert or dune

- Aquatic Biomes

- lakes and ponds

-

- Average depth

- 0.5 m

- 1.64 ft

Physical Description

Both males and females of C. diabolis have a rounded caudal fins and have no pelvic fins. The caudal peduncle, which is short and rectangular, is level with the wide-set mouth. The jaw contains one series of teeth, with 16 teeth on the upper jaw and 16 on the lower. Its scales are ctenoid, and it has no preorbital scales. Other distinguishing characteristics include a large head and eyes and an elongated anal fin. Cyprinodon diabolis has 17 pectoral rays, 12 dorsal rays and 28 caudal rays. The male is larger than the female, is irridescent blue, and has vertical bars on its tail. The female is smaller and more slender than the male, is yellow-brown in color, has a light spot on its dorsal fin, and has no bars on its tail. Cyprinodon diabolis usually does not reach lengths greater than 20 millimeters, but lengths of up to 26 millimeters have been observed during seasons where sunlight exposure is at a maximum. (Deacon, et al., 1980; Ono, et al., 1983)

- Other Physical Features

- ectothermic

- heterothermic

- bilateral symmetry

- Sexual Dimorphism

- male larger

- sexes colored or patterned differently

- male more colorful

-

- Range length

- 26 (high) mm

- 1.02 (high) in

-

- Average length

- 20 mm

- 0.79 in

Development

The life cycle of Cyprinodon diabolis follows the pattern of egg to larvae to juvenile to adult. Evidence suggests that oogenesis and egg development are temperature sensitive. When bred in a laboratory, C. diabolis eggs exhibit impeded development at water temperatures of 32 degrees C. This is also observed when oxygen levels in the water are below 70 percent saturation. In their natural habitat of Devils Hole, larvae are found in the greatest amount on the inner portion of the limestone shelf, where oxygen levels can reach as high as 100 percent saturation during the day. Larval density is low in deeper water, further indicating that the hatching of eggs is dependent on the temperature and oxygen saturation of the surrounding habitat. In addition, the rate of egg development peaks in May, when water temperatures are higher. The average growth rate of larvae is 0.65 mm a week. (Deacon and Taylor, 1994; Deacon, et al., 1980)

Reproduction

Cyprinodon diabolis exhibits a polygynous mating system, following a consort pair breeding system, defined as a gravid female being closely followed by one or more males. The male follows the female for up to one hour, and both male and female periodically move to the bottom of the pool and spawn. Although the male will prevent other competing males from interfering by coming closer to the female or blocking the intruder with his body, there is little aggressive behavior between males. (Naiman and Soltz, 1981)

- Mating System

- polyandrous

Cyprinodon diabolis can breed year round, but breeding is most intense from April to May. The fact that they can continuously breed is attributed to the constancy of the temperature of their habitat, which remains between 33.4 and 34.0 degrees C. Because of the small population of Devil’s Hole pupfish, spawning levels are higher than those in other species of Cyprinodon. Observations revealed the mean male reproductive success was 0.6 spawning per male per hour, while the maximum was 1.5 spawning per male per hour. Cyprinodon diabolis uses the limestone bedrock as well as the algae that grows on it as a substrate for spawning. It reaches reproductive age at between 8 at 10 weeks. It takes 7 days for the eggs to hatch, and the average length of a fry is 6.5 mm. Although territorial behavior is not normally observed, males will exhibit this behavior during times when population size and food supplies are lower. This occurs during the winter months, when sunlight exposure is minimal. (Naiman and Soltz, 1981; Soltz, 1979; Strecker and Kodric Brown, 1999)

- Key Reproductive Features

- year-round breeding

- gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

- sexual

- fertilization

- oviparous

-

- Breeding interval

- Cyprinodon diabolis breeds continuously throughout the year

-

- Breeding season

- Cyprinodon diabolis spawns throughout the year

-

- Average time to hatching

- 7 days

-

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

- 8 to 10 weeks

-

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

- 8 to 10 weeks

Cyprinodon diabolis exhibits no signs of parental investment past spawning. (Ono, et al., 1983; Ono, et al., 1983; Ono, et al., 1983)

- Parental Investment

-

pre-hatching/birth

-

provisioning

- female

-

provisioning

Lifespan/Longevity

The lifespan of C. diabolis is between 6 and 12 months. (Deacon, et al., 1980)

-

- Typical lifespan

Status: wild - 6 to 12 months

- Typical lifespan

-

- Typical lifespan

Status: captivity - 6 to 12 months

- Typical lifespan

Behavior

Cyprinodon diabolis exhibits very lively and energetic behavior, sprinting around the small space it inhabits. It is the only member of the pupfish that does not exhibit any territorial behavior. An exception to this is during mating, where a male will prevent other competing males from interfering by coming closer to the female or blocking the intruder with his body. However, there is little aggressive behavior between males. (Bunnell, 1970)

- Key Behaviors

- natatorial

- diurnal

- motile

- sedentary

- social

-

- Range territory size

- 17.5 to 17.5 m^2

Home Range

Cyprinodon diabolis has been called one of the most geographically isolated species in the world. Its home range is a 3.0 foot (1 m) by 5.0 foot (1.67 m) limestone bed. (Bunnell, 1970)

Communication and Perception

Although specific information on perception in C. diabolis could not be found, information regarding other members of Cyprinodon was found. Females of C. maya were able to recognize members of the opposite sex from both chemical and visual cues, while other members of Cyprinodon use either only chemical or only visual cues. (Strecker and Kodric Brown, 1999)

Food Habits

Devils Hole pupfish feed primarily on algae that grows on the limestone shelf in Devils Hole. Diatoms are the major food source in the winter and spring, while Spirogyra serve as the food source in the summer and fall. Tryonia (a small snail), a tubularian and Dugesia have also been found in the guts of small numbers of C. diabolis. Cyprinodon diabolis spends most of the time feeding on the south end of the limestone shelf. When disturbed, it migrates to the north end of the shelf, retreats to deeper water and then returns back to the shelf to feed again. (Naiman and Soltz, 1981)

- Animal Foods

- mollusks

- aquatic or marine worms

- aquatic crustaceans

- other marine invertebrates

- zooplankton

- Plant Foods

- algae

- phytoplankton

Predation

Cyprinodon diabolis is the largest known inhabitor of Devils Hole, resides at the top of the food chain, and does not have any predators. (La Rivers, 1962)

Ecosystem Roles

Although little information on the role that Cyprinodon diabolis plays in its ecosystem, it can be assumed that they control levels of algae and other small organisms in Devils Hole. This allows the environmental integrity of Devils Hole to be maintained. (Deacon, et al., 1980; Naiman and Soltz, 1981)

- There are no groups that are used as hosts by C. diabolis.

- There are no species that are mutualists with C. diabolis.

- There are no commensal species that use C. diabolis as a host.

Economic Importance for Humans: Positive

Although they have little economic benefit to humans, studies of the evolutionary patterns of C. diabolis are of interest to many students of evolutionary biology, especially the effects of small population size and geographic isolation. The mechanisms of evolution of the Devils Hole pupfish are analogous to those of Darwin's finches, which are useful for educational and research purposes. (Ono, et al., 1983)

- Positive Impacts

- research and education

Economic Importance for Humans: Negative

There are no known adverse affects of Cyprinodon diabolis on humans.

Conservation Status

Because Cyprinodon diabolis is extremely geographically isolated, has a small population number, and exhibits many unique morphological characteristics, there has been a large effort in past years to protect them and preserve their habitat. Ash Meadows had been a site for developers for many years and had exchanged hands of many owners. Environmentalists worried that development would lower the water level in Devils Hole significantly, thus destroying the habitat of C. diabolis. In 1982, the Devils Hole pupfish was named an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). This halted a plan to turn Ash Meadows into a residential area, which would have certainly affected the water levels of Devils Hole in a deleterious manner. In 1984 The Nature Conservancy (TNC) was able to purchase Ash Meadows, and the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge was created. This has allowed for the management and protection of the Devils Hole pupfish. There have also been attempts to relocate some of the population and induce spawning in other environments such as the Steinhart Aquarium in San Francisco, but they have been mostly unsuccessful. Other attempts to rear the fish in the Hoover Dam proved to be successful, but C. diabolis exhibited abnormal growth patterns not seen in fish reared in the natural habitat of Devils Hole, suggesting that is the only location that they can breed without losing their one-of-a-kind characteristics. (Deacon and Deacon Williams, 1991; Duff, 1976)

-

- IUCN Red List

-

Vulnerable

More information

-

- IUCN Red List

-

Vulnerable

More information

-

- US Federal List

- Endangered

-

- CITES

- No special status

Other Comments

Although the population of Cyprinodon diabolis is extremely small (the population varies from 200 to 800 depending on the time of year), the Devils Hole pupfish has resided in the same small area for over 30,000 years. They are perhaps one of the most geographically isolated organisms on this planet, and are so adapted to their surroundings that when bred in artificial habitats, they undergo rapid morphological changes not observed in those that live in Devils Hole. Cyprinodon diabolis has a "rate" of evolution must be extraordinary for them to exhibit so many changes in such a short geological span of time. (Bunnell, 1970)

Contributors

Sarah Stark (author), University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, William Fink (editor, instructor), University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Renee Sherman Mulcrone (editor).

Glossary

- Nearctic

-

living in the Nearctic biogeographic province, the northern part of the New World. This includes Greenland, the Canadian Arctic islands, and all of the North American as far south as the highlands of central Mexico.

- acoustic

-

uses sound to communicate

- bilateral symmetry

-

having body symmetry such that the animal can be divided in one plane into two mirror-image halves. Animals with bilateral symmetry have dorsal and ventral sides, as well as anterior and posterior ends. Synapomorphy of the Bilateria.

- chemical

-

uses smells or other chemicals to communicate

- desert or dunes

-

in deserts low (less than 30 cm per year) and unpredictable rainfall results in landscapes dominated by plants and animals adapted to aridity. Vegetation is typically sparse, though spectacular blooms may occur following rain. Deserts can be cold or warm and daily temperates typically fluctuate. In dune areas vegetation is also sparse and conditions are dry. This is because sand does not hold water well so little is available to plants. In dunes near seas and oceans this is compounded by the influence of salt in the air and soil. Salt limits the ability of plants to take up water through their roots.

- diurnal

-

- active during the day, 2. lasting for one day.

- ectothermic

-

animals which must use heat acquired from the environment and behavioral adaptations to regulate body temperature

- external fertilization

-

fertilization takes place outside the female's body

- fertilization

-

union of egg and spermatozoan

- freshwater

-

mainly lives in water that is not salty.

- herbivore

-

An animal that eats mainly plants or parts of plants.

- heterothermic

-

having a body temperature that fluctuates with that of the immediate environment; having no mechanism or a poorly developed mechanism for regulating internal body temperature.

- motile

-

having the capacity to move from one place to another.

- natatorial

-

specialized for swimming

- native range

-

the area in which the animal is naturally found, the region in which it is endemic.

- omnivore

-

an animal that mainly eats all kinds of things, including plants and animals

- oviparous

-

reproduction in which eggs are released by the female; development of offspring occurs outside the mother's body.

- phytoplankton

-

photosynthetic or plant constituent of plankton; mainly unicellular algae. (Compare to zooplankton.)

- polyandrous

-

Referring to a mating system in which a female mates with several males during one breeding season (compare polygynous).

- sedentary

-

remains in the same area

- sexual

-

reproduction that includes combining the genetic contribution of two individuals, a male and a female

- social

-

associates with others of its species; forms social groups.

- tactile

-

uses touch to communicate

- temperate

-

that region of the Earth between 23.5 degrees North and 60 degrees North (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Arctic Circle) and between 23.5 degrees South and 60 degrees South (between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Antarctic Circle).

- visual

-

uses sight to communicate

- year-round breeding

-

breeding takes place throughout the year

- zooplankton

-

animal constituent of plankton; mainly small crustaceans and fish larvae. (Compare to phytoplankton.)

References

Bunnell, S. 1970. The Desert Pupfish. California Tomorrow, Vol. 1: 2-14.

Deacon, J., C. Deacon Williams. 1991. Ash Meadows and the Legacy of the Devil's Hole Pupfish. Pp. 69-87 in W Minckley, J Deacon, eds. Battle Against Extinction. Tuscon, Arizona: The University of Arizona Press.

Deacon, J., D. Lockard, G. Kobetich, J. Radtke, H. Gunther, D. Soltz. 1980. Devil's Hole Pupfish Recovery Plan. Portland, Oregon: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Deacon, J., F. Taylor. 1994. Diel oxygen variation and hatching success of Devils Hole pupfish: An Hypothesis. Desert Fishes Council Twenty Sixth Annual Symposium, 17 to 20 November: 14.

Duff, D. 1976. "Managing" the Pupfish Proves Fruitless. Defenders, Vol. 51 No. 2: 120.

La Rivers, I. 1962. Fishes and Fisheries of Nevada. Nevada: Nevada State Fish and Game Comission.

Naiman, R., D. Soltz. 1981. Fishes In North American Deserts. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

Ono, D., J. Williams, A. Wagner. 1983. Vanishing Fishes of North America. Washington, D.C.: Stone Wall Press, Inc..

Soltz, D. 1979. "The Native Fish Conservancy Webpage" (On-line). Accessed October 20, 2004 at http://www.nativefish.org/Articles/desert.htm.

Strecker, U., A. Kodric Brown. 1999. Mate Recognition Systems in a Species Flock of Mexican Pupfish. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, Volume 12, Issue 5: 927.